Urban flooding in Pakistan refers to water accumulation in cities due to rainfall exceeding the capacity of drainage systems. The urban flooding meaning differs from traditional river floods: it is primarily a man-made disaster exacerbated by unplanned development, waste mismanagement, and weak governance.

Globally, urban flooding is on the rise as climate change alters rainfall patterns. For Pakistan, this issue is magnified by rapid population growth and a lack of sustainable urban planning. Despite contributing less than 1% to global greenhouse gas emissions, Pakistan is ranked among the top five countries most vulnerable to climate change (World Bank, 2022).

Why Does It Matter in Pakistan?

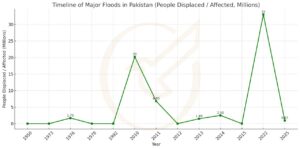

Urban flooding directly affects millions of citizens annually. It disrupts mobility, damages infrastructure, halts businesses, spreads waterborne diseases, and disproportionately impacts low-income communities. In Karachi alone, monsoon floods cause billions in economic losses each year. Nationwide, the 2022 Pakistan flooding displaced 33 million people, with urban centers among the worst affected (UN OCHA, 2022).

Thus, answering questions like “Which Pakistani city is vulnerable to urban flooding in monsoon?” becomes critical to adaptation planning. Karachi, Lahore, Rawalpindi, Peshawar, and Quetta are all high-risk zones.

Climate Change and Urban Flooding in Pakistan

Global and Regional Perspectives

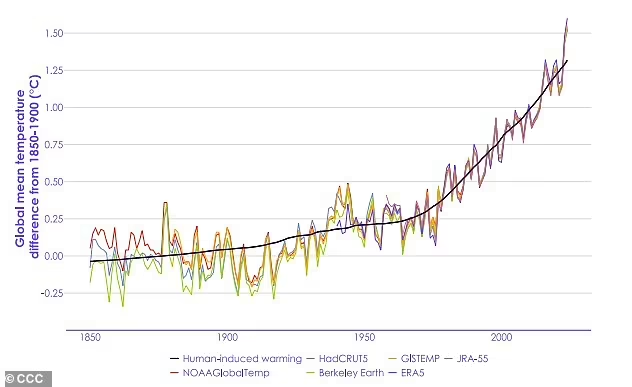

Climate change has intensified the frequency of extreme weather events such as storms, cyclones, droughts, and floods. South Asia is particularly vulnerable, with erratic monsoon patterns and rapid glacial retreat in the Himalayas threatening millions of people.

According to Pakistan’s climate data and reports from the World Bank and NDMA:

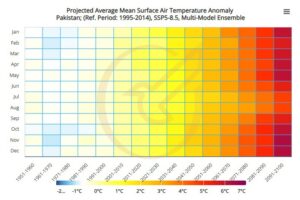

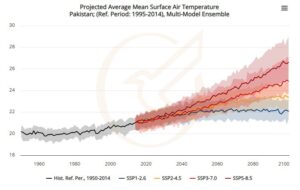

Rising Temperatures

- Pakistan’s average annual temperatures have risen by about 0.5°C since the 1960s (World Bank, 2022). While this figure may seem small, even minor shifts in long-term climate averages can have dramatic impacts.

- Higher temperatures increase evaporation rates, meaning more moisture is retained in the atmosphere, which later falls as intense, concentrated rainfall events — one of the leading drivers of flash flooding and cloud bursts in northern Pakistan.

- Heat also accelerates glacial melt in the Himalayas and Karakoram ranges, destabilizing natural reservoirs. This has already resulted in Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs), which directly affect urban settlements downstream.

Projected Warming by 2050

- By 2050, Pakistan’s average temperature is projected to rise by 1.3–1.5°C (World Bank, 2022; NDMA, 2025).

- This warming will not be uniform: urban centers like Karachi, Lahore, and Multan are expected to face more frequent heatwaves, while high-altitude regions such as Gilgit-Baltistan will experience accelerated glacial retreat.

- Warmer conditions also expand the breeding range of disease vectors, meaning urban flooding will coincide with heightened public health risks (dengue, malaria, cholera).

Erratic Rainfall Patterns

Historically, Pakistan’s monsoon season followed a predictable cycle between July and September. However, rainfall patterns have become increasingly erratic and unpredictable in recent decades (NDMA, 2025).

Cities such as Karachi and Lahore often receive months’ worth of rain in just a few days, overwhelming drainage systems. For instance, in 2020, Karachi received nearly 484 mm of rain in 72 hours, the heaviest downpour in 90 years.

Conversely, some years bring below-average rainfall, leading to urban droughts and water shortages. This duality — excessive flooding in some years, scarcity in others — makes urban planning extremely challenging.

Increasingly Vulnerable Populations

-

- Climate projections indicate that flood-exposed populations in Pakistan will increase by nearly 5 million people by 2040 (World Bank, 2022). This growth is driven not only by climate shifts but also by rapid urbanization.

- Cities like Karachi, Lahore, and Rawalpindi have seen explosive growth in unplanned settlements, often constructed on or near natural floodplains.

- These communities are disproportionately poor, lacking resilient housing or access to emergency services. Thus, when floods strike, they bear the brunt of displacement and economic loss.

- The 2022 mega floods displaced 33 million people nationwide, with a significant portion in urban centers, demonstrating the scale of this vulnerability.

Which Region of Pakistan is Experiencing Severe Problems Due to Climate Change?

Sindh and Balochistan – Prone to Monsoon Mega Floods

Sindh and Balochistan sit at the downstream end of the Indus River Basin, making them natural catchments for monsoon floodwaters. When intense rainfall occurs in the north or along river tributaries, these provinces receive the overflow.

In the 2022 Pakistan flooding, Sindh was the hardest-hit region. According to the Post-Disaster Needs Assessment (PDNA), 8 million people were displaced in Sindh alone, with more than 2.2 million homes destroyed or damaged (NDMA/World Bank, 2022). Cities like Hyderabad, Sukkur, and Thatta were submerged for weeks, while Karachi narrowly escaped a similar fate due to emergency pumping and drainage measures.

In Balochistan, flooding in districts like Jaffarabad, Naseerabad, and Sohbatpur wiped out entire villages and destroyed road infrastructure, isolating communities for months.

These provinces are particularly vulnerable because:

- Flat terrain slows drainage, leading to long-standing stagnant water.

- Weak urban infrastructure cannot handle prolonged waterlogging.

- High poverty levels make recovery slower, leaving millions trapped in cycles of vulnerability.

As climate change increases rainfall intensity, urban flooding in Sindh’s growing cities (Larkana, Khairpur, Hyderabad) will likely become more frequent and destructive.

Northern Pakistan (Gilgit-Baltistan & Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) – GLOFs and Cloud Bursts

Northern Pakistan hosts over 7,000 glaciers and more than 3,000 glacial lakes, out of which at least 33 are identified as “hazardous” (UNDP, 2022). Rising global temperatures are accelerating glacial melt, increasing the risk of Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs).

A GLOF occurs when glacial lakes, formed from melting ice, suddenly burst through their unstable natural dams. The resulting torrents sweep through valleys, destroying homes, roads, and agricultural fields in minutes. These flash floods often extend downstream into urban settlements.

In Gilgit-Baltistan and Chitral (KP), GLOFs have repeatedly washed away bridges, roads, and hydropower installations, cutting off entire towns. The 2025 monsoon season brought multiple such incidents, where flash flooding disrupted the Karakoram Highway, isolating regions like Hunza and Ghizer.

Cloud bursts add another layer of risk. In August 2025, a severe cloud burst in Muzaffarabad (AJK) and Hunza (GB) killed dozens and destroyed multiple villages within minutes. These events are unpredictable, but their frequency has increased due to climate volatility.

The risk in northern Pakistan is unique: while the population density is lower than in Sindh, the strategic importance of infrastructure (KKH, CPEC routes, dams) means that damages have a ripple effect across the national economy.

Karachi and Coastal Regions – Rising Sea Levels and Storm Surges

Karachi, Pakistan’s largest city and economic hub, lies on the Arabian Sea coast, making it doubly vulnerable:

- To monsoon rains and drainage failures (urban flooding Karachi).

- To rising sea levels and cyclonic storm surges linked to climate change.

- Over the past two decades, sea levels along Karachi’s coast have risen by 1.1 mm per year (UNDP, 2020). Combined with illegal coastal reclamation, this has increased the risk of permanent water intrusion into low-lying areas like Korangi, Ibrahim Hyderi, and Clifton’s coastal belts.

- The loss of mangrove forests — Karachi has lost nearly 200 hectares in 12 years — has removed the city’s natural flood barrier, leaving it exposed to storm surges. Mangroves act as buffers, absorbing wave energy, but their destruction for land grabbing has left Karachi defenseless.

- Climate models predict that by 2070–2100, over 1 million people in Pakistan could be exposed to coastal flooding annually (World Bank, 2022). Karachi will account for a major portion of this exposure.

- Storm surges from tropical cyclones also pose a direct threat. The 2007 Cyclone Yemyin devastated Karachi’s coastal villages, killing hundreds. With warming seas, such events are projected to intensify.

- Urban flooding in Karachi is therefore not only a product of poor drainage but also a compounding climate crisis where local governance failures intersect with global sea level rise.

Causes of Urban Floods in Pakistan in Recent Years

The causes of urban floods in Pakistan in recent years combine climatic, structural, and governance failures.

1. Cloud Bursts

A cloud burst is one of the most destructive forms of extreme rainfall. It occurs when a large amount of moisture in the atmosphere condenses rapidly and is released as torrential rain over a small geographical area in a very short time (often less than an hour). The rainfall intensity in a cloud burst can exceed 100 mm per hour, overwhelming any natural or man-made drainage system.

In Pakistan, cloud bursts have become increasingly frequent due to rising atmospheric temperatures and changing monsoon dynamics.

- In Islamabad (2021), a sudden cloud burst released 116 mm of rain in under two hours, submerging major roads and sweeping away vehicles in sectors like E-11. Dozens of homes were damaged, and at least two people died in the flash flooding.

- In Gilgit-Baltistan (2025), multiple cloud bursts in Hunza and Ghizer valleys triggered flash flooding and landslides, washing away sections of the Karakoram Highway (KKH). Entire villages were cut off, and casualties were reported in Muzaffarabad due to sudden torrents.

Cloud bursts are especially dangerous because they are almost impossible to predict and occur with little warning. Their frequency underscores how climate change is intensifying short-duration, high-intensity rainfall in Pakistan’s mountainous and urban regions.

2. Flash Flooding

Flash flooding occurs when intense rainfall or sudden glacial melt generates torrents of water that overwhelm rivers, streams, or urban drains within hours. Unlike seasonal river floods that develop over days, flash floods strike suddenly and are far more deadly.

- The Babusar Top flooding incidents (2019, 2022) stranded thousands of tourists when roads were washed away by flash torrents. Vehicles were trapped, and landslides compounded the crisis.

- In Swat (2025), at least 18 people were swept away in the “Swat River Tragedy” when sudden surges, triggered by cloud bursts and snowmelt, struck riverside communities.

Flash flooding is particularly destructive in mountain valleys (KP, GB, AJK) where narrow gorges funnel water at tremendous speeds. In urban areas like Quetta and Peshawar, poorly maintained drains and unchecked construction worsen flash flooding after intense rainfall.

3. Inadequate Drainage Infrastructure

A core driver of urban flooding in Pakistan is the failure of drainage systems to keep pace with rapid urbanization.

- Karachi’s sewerage network, much of which dates back to the British colonial era, was originally designed for a population of around 2–3 million. Today, Karachi has over 20 million residents, but its drainage system has not been expanded proportionately.

- The city relies on nullahs (stormwater drains) to carry rainwater into the Arabian Sea. However, these are chronically clogged with plastic waste, debris, and sewage. When monsoon rains arrive, the nullahs overflow, inundating low-lying neighborhoods like Korangi, Saddar, and DHA Phase IV.

- In August 2020, when Karachi received 484 mm of rain in three days, the city’s infrastructure collapsed. Electricity breakdowns lasted days, businesses shut down, and thousands of homes were inundated.

Lahore, Faisalabad, and Rawalpindi also face drainage problems, though on a smaller scale. The common issue is that stormwater drains are used for sewage disposal, creating chronic blockages that exacerbate urban flooding.

4. Encroachments

Encroachments on waterways represent one of the most visible human-made contributors to urban flooding.

- In Rawalpindi, the historic Nullah Lai has become a dumping ground for waste and is lined with illegal settlements. Each monsoon, heavy rainfall turns Nullah Lai into a raging torrent, flooding adjacent neighborhoods.

- In Karachi, the Gujjar Nullah, Mehmoodabad Nullah, and Orangi Nullah — essential for stormwater drainage — have been narrowed and blocked due to encroachments by housing colonies, shops, and even government-sanctioned projects.

Encroachment reduces the carrying capacity of drains, leading to overflow during even moderate rainfall. Although anti-encroachment drives have been launched in Karachi and Rawalpindi, they remain politically sensitive, as thousands of poor families live along these nullahs. This creates a governance dilemma: removing encroachments is essential for flood management, but it risks humanitarian backlash if not paired with resettlement programs.

5. Deforestation and Mangrove Loss

Forests and mangroves are natural barriers against flooding. They absorb rainfall, stabilize soil, and reduce runoff. Unfortunately, Pakistan suffers from one of the highest deforestation rates in Asia.

- Nationwide, forest cover is only 4.5%, far below the global average of 31%. In KP and GB, rapid tree cutting for timber and fuelwood has accelerated soil erosion, increasing the risk of flash floods and landslides in valleys.

- In Karachi, mangrove forests along the coast have been systematically destroyed due to land grabbing, industrial expansion, and pollution. According to local climate reports, the city has lost nearly 200 hectares of mangroves in just 12 years.

- This loss weakens Karachi’s natural defense against storm surges and tidal flooding, leaving coastal settlements like Ibrahim Hyderi increasingly exposed.

The destruction of forests and mangroves not only worsens flooding but also undermines biodiversity, fisheries, and livelihoods, creating a cascading socio-economic impact.

6. Unplanned Urbanization

Perhaps the most long-term driver of urban flooding in Pakistan is unplanned urbanization.

- Cities like Lahore and Karachi have expanded without effective zoning or enforcement of building regulations. Wetlands, floodplains, and agricultural lands have been converted into housing colonies and shopping plazas.

- Lahore’s DHA and Bahria Town expansions have replaced natural water retention zones with concrete. This has reduced groundwater recharge and increased surface runoff, overwhelming drainage during monsoon rains.

- In Karachi, unregulated settlements have mushroomed along drainage channels, nullahs, and even on reclaimed land near the sea. As a result, when rainfall occurs, the water has nowhere to percolate and accumulates rapidly, causing urban flooding.

Urban planning experts warn that Pakistan’s current development model is “water-blind” — it does not consider natural water flows, stormwater management, or climate resilience. Unless planning priorities change, unplanned urbanization will continue to amplify the severity of floods.

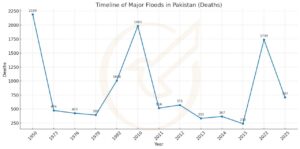

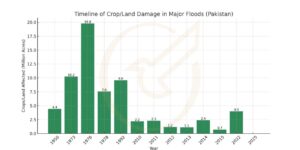

Historical Overview of Major Urban Floods in Pakistan

Major urban floods in Pakistan reveal a recurring cycle of devastation:

| Year | What happened | Affected Provinces | Affected Areas | Deaths | People affected | Housing damage | Crops / Land | Roads / Bridges | ||

| 1950 (monsoon) | Major Indus basin flooding across provinces | Undocumented | Undocumented | 2,190 | — | — | 17,920 km² flooded | — | ||

| 1973 (Aug–Sep) | Very large Indus flood | Punjab & Sindh (Indus main stem) | Historic peak flooding on the Indus between Guddu–Sukkur in 1976; 1973 & 1978 also large Indus events inundating lower Indus plains. Country InspirationADB | 474 | — | — | 41,472 km² flooded | — | ||

| 1976 (Jul–Sep) | Extreme Indus flood | Punjab & Sindh (Indus main stem) | Historic peak flooding on the Indus between Guddu–Sukkur in 1976; 1973 & 1978 also large Indus events inundating lower Indus plains. Country InspirationADB | 425 | ~1.7 million | 11,000 houses damaged (est.) | ~8 million ha inundated; 18,390 villages | — | ||

| 1978 (monsoon) | Widespread river flooding | Punjab & Sindh (Indus main stem) | Historic peak flooding on the Indus between Guddu–Sukkur in 1976; 1973 & 1978 also large Indus events inundating lower Indus plains. Country InspirationADB | 393 | — | — | 30,597 km² flooded; 9,199 villages | — | ||

| 1992 (7–11 Sep) | “Super Flood” of Jhelum/Chenab/Indus | AJK & northern Punjab (Jhelum/Chenab) | Worst along Jhelum/Chenab corridors in AJK & upstream Punjab (e.g., around Sialkot–Gujranwala belt); widespread landslides/embankment failures reported. (district examples representative of the corridor; primary source speaks to the corridor and provinces) | 1,008 | — | — | 38,758 km² flooded; 13,208 villages | — | ||

| 2010 (late Jul–Oct) | Country-wide “super floods” | All provinces (Indus main stem & tributaries | Swat, Nowshera, Charsadda, D.I. Khan (KP); Muzaffargarh, Rajanpur, D.G. Khan (Punjab); Thatta, Dadu, Jamshoro, Sukkur, Jacobabad, Khairpur, Kashmore (Sindh); Jaffarabad, Naseerabad (Balochistan) | 1,985 | ~20.2 million | ~1.4 million destroyed + ~241k damaged | ~2.2 million ha cropped area affected | — | ||

| 2011 (Aug–Sep) | Sindh-centred monsoon floods | Sindh (left bank Indus) + parts of Balochistan/Punjab | Worst in Sindh: Badin, Mirpurkhas, Sanghar, Umerkot, Tando Allahyar, Tando Muhammad Khan, Shaheed Benazirabad, Hyderabad, Thatta, Dadu (among others). ffc.gov.pkifrc.org | 516 | ~6.8 million acres area affected | ~1.6 million houses damaged | ~2.3 million acres crops | — | ||

| 2012 (Aug–Sep) | Flash & river floods (Balochistan, Sindh, south Punjab) |

|

Rajanpur, D.G. Khan (Punjab); Jacobabad, Shikarpur, Kashmore, Dadu, Kambar-Shahdadkot (Sindh); Jaffarabad, Naseerabad (Balochistan). ifrc.org+1ReliefWeb | 571 | 14,159 villages | ~636,438 houses damaged/destroyed | 4,746 km² affected | — | ||

| 2013 (Aug–Sep) | Monsoon floods (Chenab, Jhelum, Indus) |

|

Punjab: Sialkot, Narowal, Sheikhupura, Jhang, Kasur, Okara; urban flooding in Karachi/Hyderabad; KP flash/riverine in Chitral, Peshawar, Charsadda; south Punjab D.G. Khan, Rajanpur. National Disaster Management AuthorityEMRO | 333 | ~1.49 million | ~33,763 full / 46,180 partial | ~1.107 million acres | — | ||

| 2014 (Sep) | Kashmir–Punjab floods (Jhelum/Chenab) |

|

Punjab: Sialkot, Narowal, Gujranwala, Mandi Bahauddin, Hafizabad, Chiniot, Jhang; AJK: Hattian Bala, Haveli, Sudhnoti; GB: Diamir. | ~367 | >2.5 million | ~100,000 homes | >2.4 million acres crops | — | ||

| 2015 (monsoon) | Multiple river/flash floods |

|

Chitral (KP) and Ghanche, Astore, Ghizer, Hunza-Nagar, Skardu (GB) were heavily hit; later flooding moved into Punjab/Sindh lowlands. ACT AllianceOCHA | 238 | 4,634 villages | — | 2,877 km² affected | — | ||

| 2022 (Jun–Oct) | Nationwide “mega-floods” | Sindh, Balochistan, KP, South Punjab | Sindh: Dadu, Qambar-Shahdadkot, Larkana, Khairpur, Jacobabad, Thatta, Badin; Balochistan: Jaffarabad, Naseerabad, Sohbatpur, Kachhi; KP: D.I. Khan, Tank; Punjab: D.G. Khan, Rajanpur, Layyah, Mianwali. (94 calamity-hit districts nationwide.) The World Bank DocumentsReliefWebNational Disaster Management Authoritydata-in-emergencies.fao.org | ~1,739 | ~33 million (≈8 million displaced) | >2.2 million homes damaged/destroyed | >4 million acres farmland damaged (est.) | ~13,000 km roads, ~410–439 bridges damaged | ||

| 2025 (to-date, as of 19 Aug 2025) | Ongoing monsoon season impacts | Buner — Pir Baba, Gokand, Daggar; Swat; Bajaur — Salarzai; Shangla, Mansehra, Battagram, parts of Lower Dir and Abbottabad. Dawn+1 AJK (Muzaffarabad/Neelum) and GB (Hunza, Ghizer, Gilgit, Baltistan corridor) Nasirabad / Sucha Nullah cloudburst killed members of the same family; wider flash flooding around the state capital. DawnPakistan TodayAaj English TV Hunza (Gojal / Gulmit, Morkhun) — KKH (Karakoram Highway) washed out/blocked in sections; thousands stranded; power lines near Sost affected. Gilgit District — cloudburst impacts in Haramosh Valley; Naltar Highway damaged. Dawn Baltistan side — Baltistan Highway bridge damage; Astak/Astore road blockages. Ghizer, Ghanche, Skardu, Astore, Hunza, Diamer — multiple valleys marooned; KKH closures compounded isolation. Ghizer (Ghazar) — at least 10 fatalities in one incident; KKH repeatedly disrupted by slides/floods. |

707 (cumulative) | 967 injured | ~2,938 houses damaged (1,012 full / 1,926 partial); 1,108 livestock | — | ~461 km roads, ~152 bridges damaged |

Case Study 1: Karachi Flooding (2020)

In August 2020, Karachi experienced its worst urban flooding in nearly a century. The city recorded 484 mm of rainfall in just three days, the heaviest downpour in 90 years (Pakistan Meteorological Department, 2020).

- Infrastructure Collapse: Entire districts such as DHA, Korangi, Saddar, and PECHS were submerged under several feet of water. With stormwater drains and sewers choked by garbage and encroachments, roads turned into rivers.

- Power and Transport Breakdown: Karachi Electric’s grid collapsed, leaving millions without electricity for up to four days. Mobile networks, internet services, and public transport were crippled, isolating residents.

- Economic Losses: Industrial estates in Korangi and SITE were paralyzed, costing billions in lost production and exports. Informal workers such as street vendors and rickshaw drivers lost their livelihoods overnight.

- Health Impacts: Stagnant water created breeding grounds for dengue and malaria, while sewage mixing with floodwater triggered gastrointestinal illnesses.

Case Study 2: Pakistan Flooding 2022

The 2022 floods in Pakistan were among the worst climate disasters in recent global history. Triggered by record-breaking monsoon rains combined with accelerated glacial melt, they inundated one-third of the country.

- Humanitarian Crisis: According to UN OCHA, 33 million people were affected, with 8 million displaced across Sindh, Balochistan, South Punjab, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Over 1,700 people died and thousands were injured.

- Economic Impact: Damages and losses were estimated at $30–40 billion, wiping out years of economic progress. The agriculture sector was devastated: over 4 million acres of farmland were destroyed, along with cash crops like cotton and rice, leading to food shortages and inflation.

- Urban Devastation: Cities such as Hyderabad, Sukkur, Jacobabad, and Dadu remained submerged for weeks. In Balochistan, Quetta and surrounding towns were cut off due to collapsed bridges and highways. Even urban Sindh’s middle-class areas suffered unprecedented waterlogging.

- Poverty and Migration: The World Bank reported that 9.1 million people were pushed below the poverty line. Many urban families displaced from Sindh’s rural areas migrated to Karachi and Hyderabad, intensifying the burden on already fragile city infrastructure.

- International Response: The disaster prompted one of the largest humanitarian appeals for Pakistan, with aid coming from UN agencies, Gulf states, and Western governments. However, recovery remains incomplete years later.

Case Study 3: Babusar Top and GB Cloud Bursts (2025)

In the summer of 2025, flash floods and cloud bursts devastated northern Pakistan.

- Babusar Top Flash Flooding: Torrential rains triggered landslides and floods that stranded thousands of tourists along the scenic Babusar Pass. Roads were washed away, vehicles swept downstream, and rescue operations were delayed due to road closures. The incident underscored how vulnerable tourism infrastructure is in the northern highlands.

- Gilgit-Baltistan Cloud Bursts: Several districts, including Hunza, Ghizer, and Gilgit, experienced violent cloud bursts, which caused flash floods and landslides that destroyed homes, blocked the Karakoram Highway (KKH), and cut off remote valleys. Power transmission lines were also knocked out, plunging areas into darkness.

- AJK Tragedy: In Muzaffarabad and surrounding valleys, a sudden cloud burst released torrents of water that swept away homes and killed dozens of people within minutes. Entire families perished, and displacement in hilly communities rose sharply.

- Strategic Impact: The repeated blockages of the Karakoram Highway disrupted trade routes critical to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). This highlighted the national security implications of climate disasters in the north.

Impacts of Urban Flooding in Pakistan

-

Economic Impacts

Urban flooding has devastating consequences for Pakistan’s fragile economy, which is already under stress from debt burdens and low industrial productivity.

- 2022 Floods Losses: According to the World Bank and UN OCHA, the 2022 mega floods caused between $30–40 billion in economic losses. This figure includes direct damages to housing, infrastructure, agriculture, and indirect losses from halted business activity. To put this in perspective, the losses amounted to nearly 10% of Pakistan’s GDP, wiping out years of development gains.

- GDP Loss Projections: Looking forward, climate models predict that by 2050, Pakistan could face 18–20% losses in GDP due to recurring floods, heatwaves, and other climate-related disasters. Urban flooding, in particular, will affect industrial hubs and services that form the backbone of the economy.

- Industrial Shutdowns: Karachi, Pakistan’s commercial capital, contributes at least 20% of the national GDP and handles over 60% of the country’s exports through its ports. When monsoon rains paralyze Karachi, as in 2020, industrial estates like Korangi, SITE, and Landhi shut down. Power cuts and waterlogging halt production, disrupt supply chains, and reduce export revenues.

- Agriculture & Food Security: Floods destroy crops, leading to food shortages. In 2022, 4.4 million acres of crops were wiped out, affecting staples like rice, cotton, and wheat. This not only reduced farmer incomes but also led to soaring food prices in cities.

- Urban Property & Insurance Losses: Thousands of homes in Karachi, Lahore, and Hyderabad are damaged every year. Since Pakistan has limited flood insurance, families often bear the full cost of reconstruction, leading to long-term financial insecurity.

2. Social Impacts

Urban flooding has deep human consequences, displacing communities and reshaping demographics.

- Mass Displacement: The 2022 floods displaced 8 million people in Sindh alone, with a national total of 33 million affected. Urban areas like Hyderabad and Sukkur became temporary shelters for rural migrants, while Karachi absorbed tens of thousands of displaced families, further straining its fragile infrastructure.

- Urban Migration & Slums: Displaced families often settle in informal settlements on the outskirts of cities. These slums lack basic services and are often built in flood-prone areas, creating a vicious cycle of vulnerability.

- Poverty Increase: The World Bank estimated that 9.1 million people were pushed below the poverty line after the 2022 floods. Many urban poor lost jobs, homes, and assets, leaving them dependent on relief aid.

- Education Disruption: Floods destroy schools or turn them into relief camps. In 2022, over 27,000 schools were damaged or destroyed, leaving millions of children without access to education for months.

- Gendered Impacts: Women and children are disproportionately affected. During urban floods, women often lose access to maternal healthcare, while girls are pulled out of school to support families in relief camps.

3. Health Impacts

Flooding directly and indirectly worsens public health crises in Pakistan’s urban centers.

- Disease Outbreaks: Stagnant floodwater becomes a breeding ground for mosquitoes, leading to outbreaks of dengue, malaria, and chikungunya. After the 2020 Karachi floods, dengue cases surged to record levels. Similarly, the 2022 floods saw a nationwide spike in vector-borne diseases.

- Waterborne Illnesses: With sewage mixing into floodwater, outbreaks of cholera, typhoid, and diarrhea rise sharply. In rural Sindh and Balochistan, thousands of children fell ill due to contaminated water sources after the 2022 floods.

- Mental Health Stress: Flood-related displacement and livelihood loss also contribute to rising cases of depression, trauma, and anxiety, which are rarely addressed in Pakistan’s health system.

- Health Infrastructure Collapse: Floods damage hospitals and disrupt supply chains for medicines. In 2022, over 1,500 health facilities were damaged nationwide, limiting access to essential care..

4. Environmental Impacts

Flooding also accelerates environmental degradation, with long-term consequences for Pakistan’s ecosystems.

- Mangrove Destruction: Karachi’s mangroves, which once covered vast stretches of the Indus delta, are shrinking rapidly due to encroachment and pollution. Over the past 12 years, nearly 200 hectares of mangroves have been destroyed, weakening the city’s natural defense against coastal flooding.

- Wetland Degradation: Urban wetlands that once absorbed floodwater have been replaced by housing colonies and roads. Lahore’s wetlands in Ravi and Karachi’s marshlands have been filled in, reducing natural flood buffers.

- Soil Erosion in the North: In Gilgit-Baltistan and KP, deforestation has stripped valleys of their protective cover. As a result, monsoon rains cause severe soil erosion and landslides, silting rivers and worsening floods downstream.

- Biodiversity Loss: Flooding and deforestation threaten species dependent on wetlands, mangroves, and forests. Fisherfolk communities in Karachi also report declining fish stocks due to saline intrusion caused by floods.

- Carbon Sink Loss: Forest loss reduces Pakistan’s capacity to act as a carbon sink, indirectly worsening climate change and making floods even more likely.

Urban Flooding in Pakistan: Issues and Challenges

- 1. Governance Failures

NDMA, PDMAs, and city governments often overlap and lack coordination. In Karachi (2020), disputes between agencies delayed relief, showing how political rivalries undermine long-term flood planning. - 2. Data Deficiency

There is limited qualitative research for urban flooding in Pakistan, with outdated or missing rainfall and drainage data. Without modern flood modeling, cities cannot predict which areas are most at risk, leading to reactive rather than preventive measures. - 3. Public Behavior

Drains and nullahs are clogged by solid waste and sewage due to poor waste management and public dumping. This reduces drainage capacity, turning even moderate rains into major floods. - 4. Climate Uncertainty

Events like GLOFs and cloud bursts are unpredictable, striking with little warning. Erratic rainfall — extreme downpours in some years, droughts in others — makes consistent planning very difficult. - 5. Urban Poverty

Low-income families often live in high-risk informal settlements along drains and riverbeds. They lack resilient housing or safety nets, so floods not only destroy homes but also trap them in cycles of poverty and displacement.

Mitigation and Adaptation Efforts

What was the Goal of Pakistan’s Billion Tree Initiative?

The Billion Tree Tsunami (2014–2018) and 10 Billion Tree Tsunami (2019–ongoing) aimed to:

1. Reducing Deforestation

Pakistan has one of the highest deforestation rates in South Asia, with forest cover at only about 4.5% of land area. The Billion Tree Tsunami planted over a billion trees in KP and millions more nationwide. By reducing tree loss, the initiative slowed soil erosion in mountainous regions, preventing sediments from silting rivers and urban drainage systems. This directly lowers the risk of downstream flooding.

2. Restoring Watersheds

Trees play a critical role in restoring watershed health — the natural systems that collect and channel rainfall into rivers and aquifers. In northern valleys, reforestation has improved water absorption and reduced the speed of runoff during monsoon rains. This means that sudden downpours are less likely to turn into flash floods that overwhelm downstream cities like Rawalpindi or Peshawar.

3. Absorbing Rainfall and Stabilizing Soil

Forests act like sponges: their roots absorb water and stabilize soil. In areas where deforestation had left slopes barren, even small rains would cause landslides and flash floods. Reforestation efforts in KP and Gilgit-Baltistan have reduced this vulnerability, providing a buffer for urban settlements in valleys and plains. By slowing runoff, the trees help recharge groundwater while also reducing immediate flood pressure on urban areas.

4. Strengthening Climate Resilience

The program was also intended to meet international climate commitments under the Paris Agreement. By expanding tree cover, Pakistan increased its carbon sinks, which not only contributes to global emission reduction but also provides local adaptation benefits. Healthier ecosystems mean stronger resilience to climate extremes such as heatwaves, droughts, and floods.

5. Indirect Benefits for Flood Reduction

While planting trees cannot replace urban drainage systems, the Billion Tree Tsunami helps reduce the scale of flash flooding that originates in upstream valleys. For example, in Swat and Chitral, improved forest cover reduces the velocity of water rushing downstream, giving more time for cities like Nowshera or Rawalpindi to prepare. In coastal areas, mangrove restoration under the 10 Billion Tree project has also helped Karachi regain some of its natural flood barriers against storm surges.

Global Lessons: Milwaukee Flooding and Beyond

Milwaukee, Wisconsin, faced repeated episodes of urban flooding in the late 20th century, caused by aging infrastructure, rapid urban growth, and increasingly intense rainfall events. The city’s stormwater system, much like Pakistan’s, was outdated and unable to cope with the frequency and severity of modern floods. After a series of damaging floods in the 1990s and early 2000s, Milwaukee undertook major reforms in stormwater management.

Key reforms included:

- Green Roofs: Buildings were incentivized to install vegetation-covered rooftops, which absorb rainfall, reduce runoff, and lower pressure on drainage networks.

- Permeable Pavements: Roads, sidewalks, and parking lots were rebuilt using materials that allow water to percolate into the ground instead of creating runoff.

- Rain Gardens and Wetlands: Communities and households were encouraged to design landscaped depressions to capture rainwater and slowly release it into the soil.

Predictions for 2050

According to the World Bank and NDMA:

| Category | Facts / Stats | Source / Notes |

| Flood Loss Projections (2050) | Annual expected damage +47–49% compared to today | Pakistan National Adaptation Plan |

| Heatwave Exposure (2050) | +32–36% more people exposed to extreme heat | National Adaptation Plan |

| Labour Productivity (2050) | −7% to −10% from heat stress | National Adaptation Plan |

| Agriculture Yields (2050) | Overall crop yields −14% to −50%; rice −25%, sugarcane −20% | World Bank & studies |

| GDP Loss (2050) | Climate impacts may cut GDP by 18–20% without adaptation | World Bank CCDR |

| Climate Migration (2050) | Up to ~40 million South Asians displaced internally; Pakistan a hotspot | WB Groundswell |

| Urban Flooding (Karachi, Lahore, Peshawar) | Major infrastructure at risk from urban floods; drainage systems already failing | NAP & WB |

| Mangrove Loss (Karachi coast) | ~200 hectares destroyed in 12 years due to land grabbing; natural flood defense lost | Local climate reporting |

| Deforestation (KP, GB) | Rapid upstream tree-cutting intensifies floods in Swat & other valleys | Govt. reports / media |

Policy Recommendations

1. Urban Drainage Master Plans

Cities like Karachi, Lahore, and Peshawar urgently need redesigned drainage systems that reflect today’s population and rainfall realities. Karachi’s sewerage network was built for fewer than 3 million people, yet the city now has more than 20 million residents. A modern urban drainage master plan should include:

- Larger stormwater drains separated from sewage lines.

- Regular desilting and anti-encroachment drives.

- Rainwater holding basins to prevent instant runoff.

2. Green Infrastructure

Nature-based solutions are a cost-effective complement to engineering. Expanding parks, wetlands, urban forests, and mangroves increases a city’s capacity to absorb and store rainfall.

- Wetlands in Lahore can act as natural water reservoirs, easing pressure on man-made drains.

- Mangrove restoration in Karachi provides a natural defense against storm surges and coastal flooding.

- Green belts and urban forests also reduce the urban heat island effect, which intensifies storms.

3. Technology Integration

Pakistan lags behind in AI-based flood forecasting and real-time monitoring. Modern systems can:

- Use satellite data and rainfall sensors to predict urban flooding hotspots hours in advance.

- Provide SMS and app-based alerts to residents.

- Map drainage networks to identify blockages before monsoon.

4. Community Engagement

No infrastructure can succeed without public cooperation. Waste dumping into nullahs is one of the biggest reasons behind urban flooding in Pakistan. Cities must:

- Launch awareness campaigns on waste disposal.

- Provide accessible garbage collection systems to reduce illegal dumping.

- Train local communities in first-response and flood preparedness

5. Integrated Policies

Currently, Pakistan’s urban planning and climate adaptation efforts are treated as separate silos. This must change. Climate-smart policies should:

- Require flood risk assessments before approving housing colonies.

- Include climate resilience in building codes and infrastructure projects.

- Align with international commitments like the Paris Agreement and National Adaptation Plans.

Chakor Ventures’ Tree Plantation Drive

On International Plantation Day, Muhammad Bilal Khan, Executive Director of Chakor Ventures, launched a tree plantation campaign to reinforce the company’s commitment to sustainability. He said, “Flash flooding is one of the greatest urban challenges Pakistan faces today, and tree plantation is our way of restoring natural defenses against it.”

Key Features of the Initiative:

- Large-Scale Plantation: Focused on planting native and flood-resistant tree species to maximize ecological benefits.

- Urban Greening: Trees planted in and around urban centers to improve water absorption, reduce heat, and stabilize soil — directly reducing the risk of flash flooding.

- Public-Private Partnership: Demonstrates how corporate actors can complement government efforts like the 10 Billion Tree Tsunami.

- Climate Resilience Contribution: By restoring green cover, the initiative helps absorb rainfall, strengthen watersheds, and reduce the urban heat island effect.

Why It Matters:

Urban flooding in Pakistan is not just a government issue — it requires collective responsibility. Chakor Ventures’ plantation drive is a step toward building climate-smart cities, setting an example for other corporations to integrate environmental action into their business strategies.

Conclusion

Urban flooding in Pakistan has evolved from a seasonal nuisance into a national climate emergency. The major urban floods in Pakistan over the decades illustrate a worsening trajectory, where every decade brings deadlier disasters. Karachi, Lahore, and Rawalpindi remain especially vulnerable, while northern Pakistan faces catastrophic flash flooding from cloud bursts and glacial melts.

Without comprehensive reforms, Pakistan risks repeating humanitarian crises like the 2022 mega floods and the ongoing 2025 monsoon tragedies. The path forward lies in climate-smart infrastructure, governance reforms, and community-based resilience, supported by science-driven qualitative research for urban flooding in Pakistan.

References

- Mustafa, Z. (2010). Climate Change and Its Impact with Special Focus in Pakistan. NESPAK Symposium.

- World Bank. (2022). Climate Change in Pakistan: Facts & Figures. Washington DC.

- NDMA & UN OCHA. (2022–2025). Pakistan Flooding Data & Climate Change Predictions. Islamabad.

- UNDP (2022). Glacial Lake Outburst Floods in Gilgit-Baltistan.

- ReliefWeb (2022). Pakistan Flood Response Plan.